Zombie Statistics, Part 1

By Steven S. Vrooman

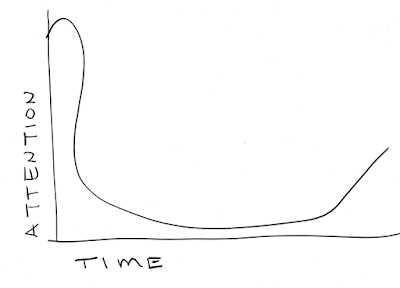

In the new edition of The Zombie Guide to Public Speaking, I added a chapter on the ways we fail to do our research. I decided to share a part of that chapter, from a section I call "Zombie Statistics," because the world needs to know the problematic history of this Curve of Attention. It is the prime example of something fake we believe because it is in graphical form. Public speaking textbooks, slideshares, blog posts, tweets . . . it is EVERYWHERE! It took me a few months of interlibrary loaning to gather enough resources to debunk it, but here it is:

In the new edition of The Zombie Guide to Public Speaking, I added a chapter on the ways we fail to do our research. I decided to share a part of that chapter, from a section I call "Zombie Statistics," because the world needs to know the problematic history of this Curve of Attention. It is the prime example of something fake we believe because it is in graphical form. Public speaking textbooks, slideshares, blog posts, tweets . . . it is EVERYWHERE! It took me a few months of interlibrary loaning to gather enough resources to debunk it, but here it is:

The Curve of Attention

This

thing has been trotted out for years. We believe it because it makes sense. I

even suggested it might have some merit in Chapter 6. The audience pays the

most attention to us at the beginning, gets sleepy and then wakes up at the

end. Here’s Sam’s version of it:

Each

version has a slightly different shape to The Curve. The reason is that there

is no actual data to back this up.

I first saw this while writing the teacher’s

manual (Vrooman & Egan, 2009) for Fraleigh & Tuman (2009), where the authors

suggest that it is based on a “Study by TCC Consulting (San Francisco, Calif.),

undertaken between 1987 and 1997” (p. N-4). Emails to the authors about this

data never got a response. I found The Curve again in Kenny (1982), who

suggests it is a result of studies conducted on students. The y axis of his

graph is labelled as “Percentage of class paying attention” (p. 13), but he

then describes some uncited experiments about how much students can recall after lectures of different

lengths, which is a different sort of y axis entirely.[1]

He cites Mills (1977) as the source of The Curve and the research behind it,

but when I finally tracked down a copy of Mills’ book, his Curve, exactly the

same as Kenny’s, is based not on data, but on “an analogy between the learning

process and the process of digestion” (p. 18).

A

digestion analogy. Really?

What

he suggests about this analogy makes intuitive sense, which is why people keep

reproducing it, but what we have is something that has become “fact” for us

only because it got turned into a graph. And Mills is reasonably clear that

this is just a thought-experiment and analogy: “the shape of the curve in the

hands of a good instructor can be modified almost at will” (p. 19).

I

later found McGrath’s (2015) citation that The Curve is based on Bligh’s (2000)

book, first published in 1971. Bligh bases almost all this on Lloyd’s (1968)

work, creating a series of diagrams based on what Lloyd “hypothesizes” and

“confirms” (Bligh, 2000, p. 49). The trouble is that Lloyd’s two-page article

is based on his own observations of student restlessness in his classes, hardly

sufficient rigor to “confirm” a hypothesis and graph the data.[2]

Yet,

by now The Curve is used as if it were a classic

study, you know, with data behind

it. Red Magma (2009) tosses their version into a Slideshare which sells their

elearning consulting. They use it as the central

data point for why lectures are an inefficient method of learning. Sharpe

(2012) suggests The Curve is an “amalgam of all sorts of things from

physiological responses to recall about part of the session.” She cites

additional “numerous studies” on our 10-15 minute attention spans in “passive

tasks” like lecture. This is a commonly reported statistic that, according to

Wilson and Korn (2007) has no real supporting evidence besides personal

experience and anecdotes.

The

fun of all of this is that writers keep changing the shape of The Curve for

their own purposes while still asserting that it is based on data. Fraleigh and

Tuman’s (2009) Curve jumps up a bit

higher at the conclusion than the 50%-ish in Mills’ (1977). Niemantsverdreit

(n.d.) has a curve that goes to 100% attention really quickly at the

introduction and then never seems to get up to 50% again.[3]

McGrath (2015) has another like it. Sharpe’s remains really flat at the end,

popping up to what we might imagine is about 20% at best. In contrast to these

attention skeptics, MichCommunication (2012) gives us a graph that looks like a

bowl, with the conclusion optimistically popping up to what looks like is even

over 100%! Reimold and Reimold (2003) have a graph that pops up to the 100% at

the end, but really sharply. Like the one I commissioned for this chapter, it

looks to be drawn by hand.[4]

If

I see you presenting this Curve of Attention as a fact you will lose just about

all of your credibility with me. This graph is reproduced because visual aids

seem “truthy.” It is what happens when people do simple searches to find

something they want to say and need simple support. Everyone just needs to do

better research, especially in professional contexts. The Internet makes it

easier to find zombie statistics, but it makes it easier to debunk them, as

well.

[1] I was going to reprint the graph for you, but it turns out that

reprinting one graph from a book 30 years out of print would cost me more than

$150. Since I’m trying to keep this book as inexpensive as possible, that

wasn’t going to happen. Welcome to the ins and outs of self-publishing! You

can, if you’d like, go to Google Books and search “Peter Kenny attention curve”

and see the famous graph for yourself, though.

[4] If you Google “Attention Curve” you will see these versions and many

others. You will also see some distressing examples of The Curve being adapted

to other contexts, especially for Internet content audiences. The virus

spreads…