Leadership and Fear

by Steven S. Vrooman

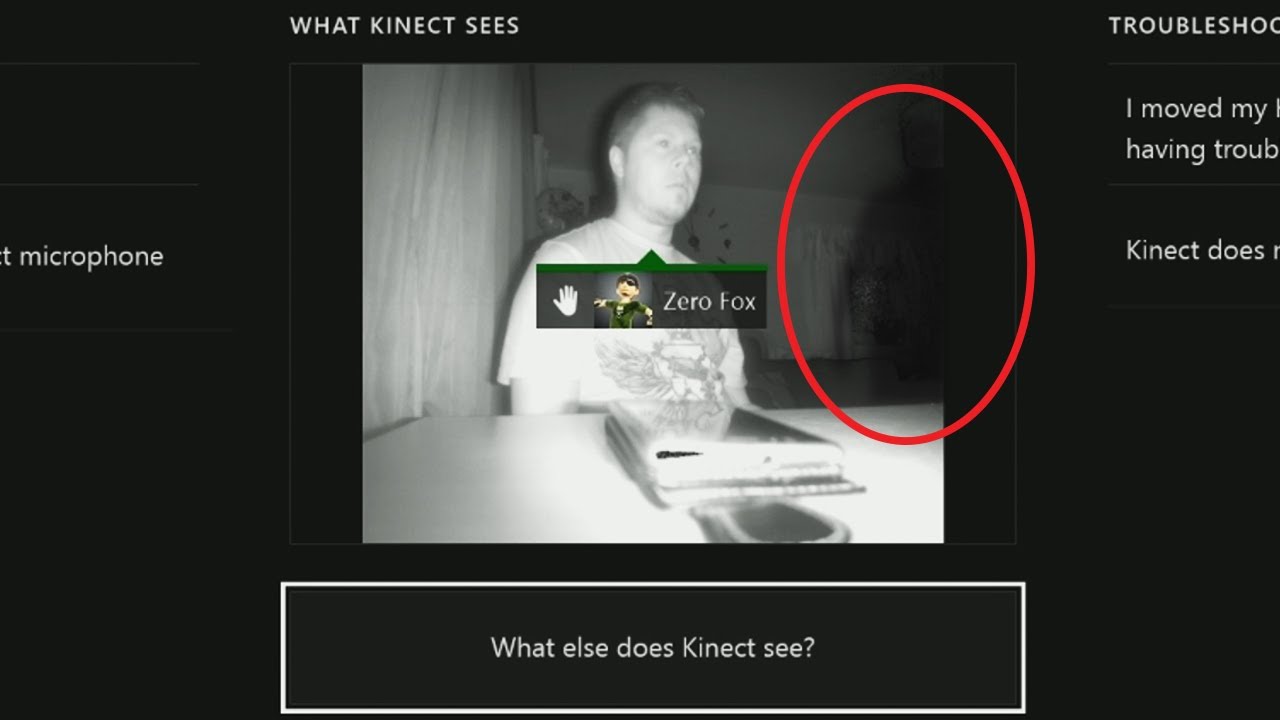

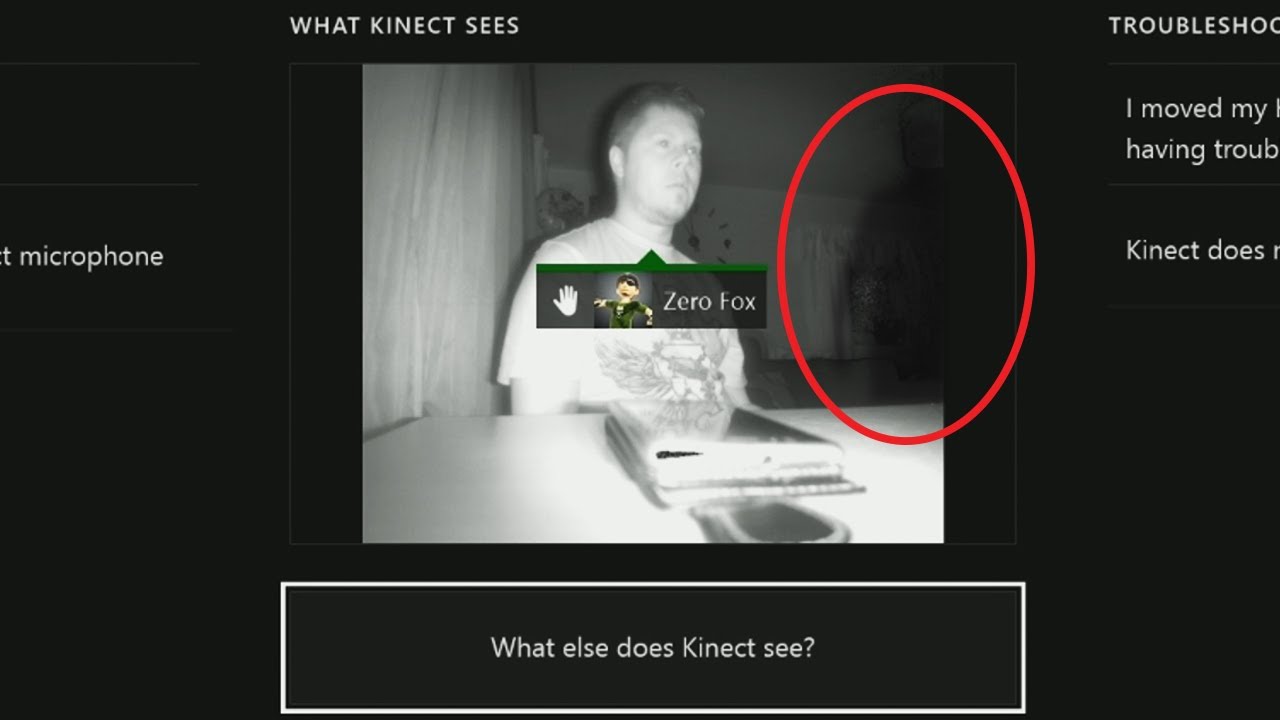

A specter is haunting our social media.

Leadership is a hard nut to crack. A cottage industry of keynote speakers is possible because we seem to have an enduring appetite for new takes on the subject. One of the key books on the subject, which I used as my textbook last time I taught a leadership class, defines it like this:

On the one hand, yes, sure, that sounds about right. On the other, well, like, dude, um, that doesn't help us an awful lot, really.

So, perhaps leadership is what Michael Calvin McGee (1980) called an <ideograph>. Later scholars in the field started using those < > symbols to designate ideographs in a more marked way than simple quotation marks, in case you were wondering. Classic examples of ideographs are things like <freedom> and <justice> and even <America>, or, in some recent work I'm doing with some colleagues, perhaps even <geek> and <nerd>. An ideograph is an abstraction that is used for its lack of specificity as a tool for persuasion or manipulation.

For example, if everyone wrote down what <privacy> meant on a sheet of paper and we stacked them together, we'd find some commonalities, but there would be lots of differences. The basic one I can think of is the classic "freedom from..." version of privacy (the 4th Amendment, search and seizure, Miranda rights, etc.) and "freedom to...", which is what the Supreme Court uses in cases involving personal sexuality and abortion, for example. And there would be many other differences, as well.

The reason for ideographic use in politics is obvious, right? We can all act like we all agree on something, even if we really don't believe all the same things, or maybe even any of the same things.

<Leadership> is an abstraction we use to, well, what exactly? It's not a political term, or like <Chicano>, (Delgado, 2009) or <nerd> a badge of collective identity. If leadership is an ideograph, I think it is more defensive. We keep it broad so that we all can pretend to be one.

The implications of that idea are far-reaching, but for this post I'd like to highlight one in particular that emerged in the wake of the 2016 presidential election.

Immediately after Election Day, social media was awash with political yelling. Even stodgy old LinkedIn. Adam Prybelski wrote a since-deleted piece pointing out. It was shared almost 35,000 times before it was deleted.

Reasonable enough, I suppose.

But I keep seeing those political rants reform themselves into hidden barbs, many of which are now taking the form of opinions on leadership, which is part of the insidious process by which ideographs are used.

I saw many updates and articles on LinkedIn from folks on the right who complained about millenials scared of the results of the election, hiding, like children, in their safe spaces, too scared to come and face reality. I saw similar things from folks on the left, who complained about boomers and gen-xers on the right who were too afraid of diversity, women, a changing economy, a changing world, life outside of gated communities or rural areas filled with sameness and seeming safety.

These insults were interesting because they almost always nestled in larger articles or posts on professional issues. That usually concluded with the author's thoughts on how this demonstrated failed leadership. Convenient hook to make sure no one cites Prybelski at you, but it is also, in this contentious hour, a particularly revelatory choice.

We may not know what leadership is, but we know what it is not -- FEAR.

Even though both sides are overly simplistic in their attacks on the other side, perhaps this connection with fear can be of use to us. Here's the thing about ambiguities and abstractions, they are haunted. In this case <leadership> is haunted by the specter of <fear>. This haunting metaphor, used by sociologist Avery Gordon (1997), is evocative. Think of possession. We are controlled by unseen entities and forces. Fear is the absent gravitational, tectonic, parapsychological force that propels what we think of when we think of leadership.

But we can't or won't admit that that's what we're thinking. We're not supposed to imagine leadership might really be so basic, to use the millenial jargon.

Underneath its ideographic exterior, used to manipulate and argue and build keynotes, is it possible that leadership, if we were more honest with the ghosts that haunt us, is more accurately defined as "a structured process of guiding effective collective response to fear"?

This has uses in various contexts. When things are going badly we are afraid of what might happen. When things are going well we are afraid it will stop or slow and we will be left behind. Hundreds of examples come to mind immediately, in all sorts of contexts.

We all seem so subject to this fear, this haunting. We all keep wanting to define leadership as a fragile thing that keeps spinning, but limited inside the hamster wheels of our own politics, our own fears, our own ghosts.

We are afraid. Mostly of each other.

And we are using <leadership> as an ideographic hammer to try to fit all the complexity we are afraid of into little boxes that we already understand. This makes us feel smart and adult and important and like we are doing something outside of the fake-news echo chambers or our overly winnowed Facebook feeds. And we are looking for extra <business> type words that can help us to feel like we can offer the world something different going forward in this new environment of tenseness we are all afraid of. But we're just repackaging the chaos into the old packages, like sending a return back to Amazon with new tape over the torn cardboard and the weak spot where we pulled off the old label.

Let's stop. This structured process of guiding you through this fear begins like this - simply.

If we can agree, together, in these complex times, that this idea about leadership we have been saying to each other without knowing it is something interesting about leadership we can actually agree on, that's a good start.

Maybe we should brainstorm together for a bit on what we can do next with that idea.

|

| You will be haunted by three spirits. . . |

Leadership is a hard nut to crack. A cottage industry of keynote speakers is possible because we seem to have an enduring appetite for new takes on the subject. One of the key books on the subject, which I used as my textbook last time I taught a leadership class, defines it like this:

It is a complex, multidimensional process that is often conceptualized in a variety of ways by different people. (Northouse, 2012, p. 9)

On the one hand, yes, sure, that sounds about right. On the other, well, like, dude, um, that doesn't help us an awful lot, really.

So, perhaps leadership is what Michael Calvin McGee (1980) called an <ideograph>. Later scholars in the field started using those < > symbols to designate ideographs in a more marked way than simple quotation marks, in case you were wondering. Classic examples of ideographs are things like <freedom> and <justice> and even <America>, or, in some recent work I'm doing with some colleagues, perhaps even <geek> and <nerd>. An ideograph is an abstraction that is used for its lack of specificity as a tool for persuasion or manipulation.

For example, if everyone wrote down what <privacy> meant on a sheet of paper and we stacked them together, we'd find some commonalities, but there would be lots of differences. The basic one I can think of is the classic "freedom from..." version of privacy (the 4th Amendment, search and seizure, Miranda rights, etc.) and "freedom to...", which is what the Supreme Court uses in cases involving personal sexuality and abortion, for example. And there would be many other differences, as well.

The reason for ideographic use in politics is obvious, right? We can all act like we all agree on something, even if we really don't believe all the same things, or maybe even any of the same things.

<Leadership> is an abstraction we use to, well, what exactly? It's not a political term, or like <Chicano>, (Delgado, 2009) or <nerd> a badge of collective identity. If leadership is an ideograph, I think it is more defensive. We keep it broad so that we all can pretend to be one.

The implications of that idea are far-reaching, but for this post I'd like to highlight one in particular that emerged in the wake of the 2016 presidential election.

Immediately after Election Day, social media was awash with political yelling. Even stodgy old LinkedIn. Adam Prybelski wrote a since-deleted piece pointing out. It was shared almost 35,000 times before it was deleted.

Reasonable enough, I suppose.

But I keep seeing those political rants reform themselves into hidden barbs, many of which are now taking the form of opinions on leadership, which is part of the insidious process by which ideographs are used.

I saw many updates and articles on LinkedIn from folks on the right who complained about millenials scared of the results of the election, hiding, like children, in their safe spaces, too scared to come and face reality. I saw similar things from folks on the left, who complained about boomers and gen-xers on the right who were too afraid of diversity, women, a changing economy, a changing world, life outside of gated communities or rural areas filled with sameness and seeming safety.

These insults were interesting because they almost always nestled in larger articles or posts on professional issues. That usually concluded with the author's thoughts on how this demonstrated failed leadership. Convenient hook to make sure no one cites Prybelski at you, but it is also, in this contentious hour, a particularly revelatory choice.

We may not know what leadership is, but we know what it is not -- FEAR.

Even though both sides are overly simplistic in their attacks on the other side, perhaps this connection with fear can be of use to us. Here's the thing about ambiguities and abstractions, they are haunted. In this case <leadership> is haunted by the specter of <fear>. This haunting metaphor, used by sociologist Avery Gordon (1997), is evocative. Think of possession. We are controlled by unseen entities and forces. Fear is the absent gravitational, tectonic, parapsychological force that propels what we think of when we think of leadership.

But we can't or won't admit that that's what we're thinking. We're not supposed to imagine leadership might really be so basic, to use the millenial jargon.

Underneath its ideographic exterior, used to manipulate and argue and build keynotes, is it possible that leadership, if we were more honest with the ghosts that haunt us, is more accurately defined as "a structured process of guiding effective collective response to fear"?

This has uses in various contexts. When things are going badly we are afraid of what might happen. When things are going well we are afraid it will stop or slow and we will be left behind. Hundreds of examples come to mind immediately, in all sorts of contexts.

We all seem so subject to this fear, this haunting. We all keep wanting to define leadership as a fragile thing that keeps spinning, but limited inside the hamster wheels of our own politics, our own fears, our own ghosts.

We are afraid. Mostly of each other.

And we are using <leadership> as an ideographic hammer to try to fit all the complexity we are afraid of into little boxes that we already understand. This makes us feel smart and adult and important and like we are doing something outside of the fake-news echo chambers or our overly winnowed Facebook feeds. And we are looking for extra <business> type words that can help us to feel like we can offer the world something different going forward in this new environment of tenseness we are all afraid of. But we're just repackaging the chaos into the old packages, like sending a return back to Amazon with new tape over the torn cardboard and the weak spot where we pulled off the old label.

Let's stop. This structured process of guiding you through this fear begins like this - simply.

If we can agree, together, in these complex times, that this idea about leadership we have been saying to each other without knowing it is something interesting about leadership we can actually agree on, that's a good start.

Maybe we should brainstorm together for a bit on what we can do next with that idea.